Shelter, Tradition, and Home

Micaela’s Family Story. Written by Vang Yang, Housing & Shelter Case Manager (Pictured)

Using culture and family tradition, Micaela leads her family’s journey from homelessness to housing.

![]() Living in shelter, families must often ‘give up’ the norms which define them and their culture. Born in Mexico, Micaela and her husband moved to the U.S.A. in 1999 to flee the violence that was happening in their hometown.

Living in shelter, families must often ‘give up’ the norms which define them and their culture. Born in Mexico, Micaela and her husband moved to the U.S.A. in 1999 to flee the violence that was happening in their hometown.

During their 22 years in the U.S.A., Micaela and her husband had six children. For 10 years the family worked at horse racing events, living at the stables and caring for the horses. Micaela shared that the entire family worked and enjoyed this lifestyle. It provided a good flow of income, stability for the parents to support the children in school, and a sense of family pride. The family was known and respected in the horse racing and hospitality industry for their skills and knowledge of horses.

Micaela became a single parent when her husband left for Mexico to care for his sick and elderly father. A two-week visit turned into a couple months and soon, due to COVID, her husband had no way of returning to the states.

The horse racing industry slowed down and closed temporarily, due to COVID as well. Micaela’s family, no longer able to remain housed at their place of employment, the horse park, found themselves experiencing homelessness. For the first time in her life, Micaela did not have safe and affordable housing.

When I first met Micaela, the family had no income or housing. Micaela, who spoke limited English, for the first time in her life became the primary decision maker for their six children ages 5 to 17 years old, at the same time worrying about her husband’s safety.

According to the Minnesota Council of Latino Affairs, Latino and BIPOC households are more likely to be renters paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent and other housing costs than white households.

Additionally, it found that Latino individuals are more likely to work in the hospitality industry, which was hit hard by the pandemic and resulted in many losing their jobs.

![]() When families join Beacon’s shelter program at Families Moving Forward, we listen to the parents and learn about family culture and norms. Micaela shared with me how food was love, tradition, and memory making for her family. She laughed and smiled wide as she described a time when her husband and son were sick.

When families join Beacon’s shelter program at Families Moving Forward, we listen to the parents and learn about family culture and norms. Micaela shared with me how food was love, tradition, and memory making for her family. She laughed and smiled wide as she described a time when her husband and son were sick.

She brought home some vegetable soup from the grocery store to help with their colds. However, they refused to eat any of the store-bought soup; they only wanted to have the chicken fideo soup, homemade by Mom. After eating the soup, their colds were gone. For Micaela, food always brought her family together and it was a way to show love.

Working hard to support her family while in shelter, she secured a position working nights. Micaela shared with me that given her youngest child’s medical needs, waking up frequently and her night shift, she’d only receive an average of three to five hours of sleep each night. Like many families, her oldest child would help Mom care for the younger siblings.

Families experiencing homelessness often are working against the pressure of government policies, individual attitudes and biases which keep them homeless or in compromised living situations. BIPOC individuals experience the bias of homelessness compounded by racism.

Our job at the shelter is to partner with families to secure housing and successfully navigate these social and systemic barriers. Micaela’s family faced countless barriers ranging from her limited English skills, being Mexican born, having no rental history, and having a large family. My role with her was to support their efforts moving Micaela’s family into stable housing.

Living in shelter often challenges the role of a parent and contributes to an imbalance of power in the parent-child relationship. Research on homelessness and family relationships by Elizabeth Lindsey provides some insight.

She describes that the disciplinarian role from the parent/caretaker is compromised by shelter policies and interactions with shelter staff. This can lead to children seeing their parents as less capable in decision making and creates another level of complexity for parents who have children that are older particularly when, as with Micaela, the parent speaks limited English.

Working with Micaela, I listened and learned about her family culture, norms, and unique situation. Together, we created a pathway to support her, and relied on a professional English/Spanish translator, rather than asking her children to help translate, when it came to communication on important matters. This strategy allowed Micaela to be in control and comfortable in communicating information with me versus having her children take the lead to do so.

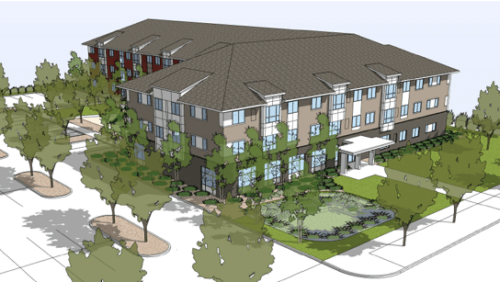

![]() Pictured left, the FMF playground where her children would have the space to play.

Pictured left, the FMF playground where her children would have the space to play.

Ensuring her children were focused on their studies, rather than assisting in Mom’s ongoing housing search, volunteer tutors worked with her children. According to Volunteers of America, children of families who are living in a shelter may lose up to a year of learning. Luckily, this wasn’t the case for Micaela’s family.

Click here to read more about our Families Moving Forward tutor volunteers.

For Micaela, food and meal preparation was core to their family culture. With a full kitchen at the program center, Micaela and her children were able to continue some of these traditions through food. Micaela would often make traditional home cooked Mexican meals for the families and staff at FMF.

The aroma and spices filled the entire building. Each meal was always different, filled with the love she put in. I recall the unique taste that came with each meal, the smiles, and the discussions we all had together. As I worked with the family over the months, I watched each of Micaela’s children grow as they continued their family traditions despite being in shelter.

The efforts to secure housing for Micaela’s family were daunting. Despite having a housing subsidy, Micaela was denied housing over and over. In many cases, the family was denied due to the size of their family and the income qualifications of meeting three times the monthly rent.

In Carver and Scott County, a family of seven needed a four-bedroom unit to meet the basic qualifications. The average rent for a four-bedroom home in Chaska and Carver County is $2,148. Which means that Micaela needed to earn $6,444 a month to qualify for housing.

An article by the Minnesota Council on Latino Affairs reveals that Latino immigrants who had language and documentation barriers had more difficulty in passing background checks and meeting housing qualifications to move into safe housing. Some landlords, who did not have the best interest of families like Micaela’s in mind, took advantage of language barriers and documentation issues by denying housing or charging extra fees. This was Micaela’s experience as well.

My colleagues, volunteers, Micaela, and her older children worked creatively to communicate with landlords in their housing search. Collectively, we made an estimated 500 calls to properties in the community.

In the circumstances where Micaela did earn three times the rent, she’d be told the unit was no longer available, with the landlord insisting the eviction moratorium prevented them from moving new families in.

Her adult daughter, who is fluent in English, and I would make calls to some of those same properties who had previously told Micaela there was no availability. We’d hear different results and learn that the property was still available for rent.

In Hennepin and Ramsey County, Micaela did not experience much of the same racial bias from landlords who heard her accent. However, the drive from the city to her job in Chaska was more than 45 minutes. The cost of gas for this drive was more than she could afford. She just couldn’t afford to live too far from her employment.

Facing these inequities head on, Micaela was promoted at her job and became a full-time employee who received health benefits. She’d quickly grow to be an asset to her employer, providing translation support to supervisors and help other Spanish speaking employees complete work assignments.

Her monthly income was now just below the $6,444 threshold she needed to qualify for a four-bedroom rental at three times the rent in Scott and Carver Counties. And as Micaela’s daughter turned 18 years old and employed part time, their combined income was over $6,444. Micaela would share with me how proud she was of increasing her income, celebrating how far she’s come.

Discussing the ideal home for her family, Micaela shared how she’d love to have a 5-bedroom house with a washer and dryer, a place for the kids to hangout in their own areas, a fenced in yard so the two youngest can play outside while Mom gardens, and of course a big kitchen with cabinets to keep spices.

One day while I was out of the office, I called the FMF Program Center to speak with my co-worker Rebekah. In the background, I could hear the excitement coming from the kids. There was laughter, celebratory shouting, and sounds of joy! Micaela had successfully found housing! A three-bedroom house near her work, with a washer and dryer, a garage, and a backyard. Everything they needed in a home!

Now stably housed, Micaela’s children have bedrooms of their own to sleep, play and study in. She had time to focus on supporting her children in school events and begin taking steps to bring her husband home to Minnesota. She is looking forward to spending the upcoming holidays together with her children in their new home with home-cooked meals, happily gathering around the table.

The support of congregations and volunteers brings unique touches to Families Moving Forward. Volunteers provide tutoring support, deliver daily meals to families, and supply groceries. We are thankful and grateful for the partnership of so many who commit to supporting families.

As a team at Families Moving Forward, we work together to advocate for families like Micaela’s. It takes sustained giving and a commitment to home to make this work a reality. Click here to get involved and make a gift to help see that families like Micaela’s receive the support they deserve.